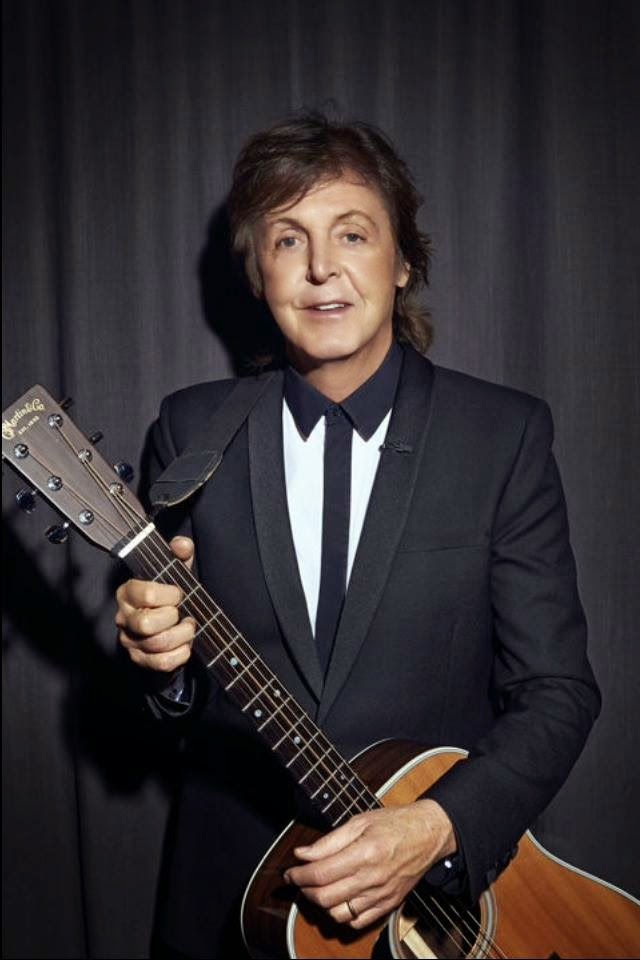

An in-depth conversation about Sir Paul's latest dance-music experiments, why he has no plans to retire from touring, and what it was really like to be a Beatle

In late May, when Paul McCartney canceled or postponed

12 dates on his Out There world tour – citing doctor's orders to rest

up after being briefly hospitalized for a mystery virus in Tokyo – many

fans were concerned. McCartney wasn't. "People say to me, 'Aw, that must

have been terrible for you.' Well, no, actually," the former Beatle,

72, tells Rolling Stone. "No one ever tells me to rest! It was like summer holidays in school or something. I thought, 'Yeah, I can get into that.'"

In late May, when Paul McCartney canceled or postponed

12 dates on his Out There world tour – citing doctor's orders to rest

up after being briefly hospitalized for a mystery virus in Tokyo – many

fans were concerned. McCartney wasn't. "People say to me, 'Aw, that must

have been terrible for you.' Well, no, actually," the former Beatle,

72, tells Rolling Stone. "No one ever tells me to rest! It was like summer holidays in school or something. I thought, 'Yeah, I can get into that.'"

McCartney says the time off from the road let him catch up on all

kinds of pursuits that his heavy touring schedule might have otherwise

made difficult. "I just took it really easy at home in England," he

says. "My son-in-law had a film script – plenty of time to read that. I

started jogging a bit. The weather was great, so that was cool. And then

I went into my recording studio and did some music that I didn't have

to do, some experimental stuff. That was a really nice musical

awakening, and it made me feel better."

The day after his triumphant return to the stage in Albany, New York, McCartney called RS

for a wide-ranging, hour-long conversation. He talked about how he

spent his time off from the road – including those studio experiments

and a trip to Ibiza with wife Nancy Shevell – and shared memories of

going to rock shows as a boy in 1950s Liverpool, what people get wrong

about John Lennon, and much more.

Tell us more about the music you were working on.I

have a studio about 20 minutes away from where I live, and sometimes

I'll go in and work on my computer. Even though I'm not really a

computer guy, I have a music program that I've worked on for years,

called Cubase. It's incredibly addictive – I'll just sit there for six

hours, until someone has to nudge me and say, "Go home now." Normally I

work on my orchestral side on that, but someone said to me, "You know

what? That's not technically an orchestral program. It's more of a pop

program." So when I had some time to do nothing, I went in and said,

"Great. I'll start on a dance track or something."

I also got a sequencer, which I was revisiting from years ago. I did an album called McCartney II [in

1980],where I had experimented with sequencers and synths in their

early days. I wanted to get back into that, but I really hadn't had much

time before. So I hooked that up with Cubase. It was really cool. I'd

get the BPM on the sequencer, match it on the computer, put some drums

in from the computer, put that all down onto Pro Tools, and screw it all

up – because it was for nothing.

Over a week, I did a couple of tracks, and that reawakened my musical

taste buds. I was really happy with those. They were just funky little

experimental things, instrumentals. The first one I did was kind of

African, so I gave it the working title "Mombasa." The next one was

faster, and that one I called "Botswana." It was a good week. It was

funny, I was talking to Joe Walsh about this. He said, "Yeah, man,

that's the best – when it's for nothing and it's not important and it's

just experimental, you have the most fun. It's really good for your

soul, that stuff.' And I agree. It was very freeing.

Do you listen to much dance music these days?You

know, I listen to it on the radio. I have a friend who, for years now,

has done a compilation for me of dance tracks and new releases. I play

them while I'm cooking or in the car, and just see what interests me,

see who's doing what. I'll have tracks like Pharrell's "Happy" way

before it's broken onto the scene, and say, "Oh, that's a pretty catchy

one. That's going to be a hit." I hear a lot of dance music that way.

Do you listen to much dance music these days?You

know, I listen to it on the radio. I have a friend who, for years now,

has done a compilation for me of dance tracks and new releases. I play

them while I'm cooking or in the car, and just see what interests me,

see who's doing what. I'll have tracks like Pharrell's "Happy" way

before it's broken onto the scene, and say, "Oh, that's a pretty catchy

one. That's going to be a hit." I hear a lot of dance music that way.

Funnily enough, one part of this rest program was, I said to Nancy,

"Hey, we can take a holiday! A real holiday, where we go away." So we

went away to Ibiza. Obviously, there's a lot of dance music there. We

didn't exactly go clubbing, but there's plenty of it about. It's in the

air in that place. The house we rented didn't have a good sound system,

so I said, "Excuse me, we're in Ibiza. I've really got to be able to

hire a sound system." So I found the right guys, and they showed up and

got me a really great little system. We were saying, "We could rent this

house out one evening for 600 people, and we could have a rave." [Laughs] We didn't do it, but I was playing that music that I'd done in the studio, and it sounded pretty good.

Do you have any plans to go back to the studio and record more?Yeah,

I've got a lot of songs that I've written, and some that I need to

finish. There's no fixed date, but at the back of my mind, I'll be

wanting to clear a few months for me to write up the most likely of the

songs that I've got on the boil and figure out how I want to record them

and what I want to do with them. But I haven't booked any studio time.

It's all there as fun for the future.

Now you're back on the road, on a tour that's been rolling for more than a year. What keeps you going?Well,

I'm always reminded of when I was a kid and I used to go to shows. This

was pre-pre-pre-Beatles. I was just a little kid in Liverpool with no

money, and I'd be saving up forever. It'd be really good if the show

satisfied me – and it really pissed me off if it didn't. So I have this

thing, which is that these people have paid money. They're not

necessarily all going be that flush, so let's give them a good night

out. Let's have a party. Let's make it a fiesta kind of thing, so

everyone goes home and thinks, "Yeah, I didn't mind spending that

money." That's the philosophy behind a lot of what I do.

One of the first concerts I ever went to was a Bill Haley concert. I

was so young, I was still in short trousers. I was about 13 or

something. It was rock & roll coming to Liverpool, and I was so

excited. I saved up, got this ticket, went to the Liverpool Odeon – and

the whole first half wasn't Bill Haley! It was this other guy who, years

later, I learned was a promoter who had his own band. Mind you, the

second half, when Bill opened from behind the curtains with, "One, two,

three o' clock, four o'clock rock," and did "Rock Around the Clock,"

which is almost the birth of rock & roll – okay, that was exciting.

The curtains opened and they're all there in these crazy tartan jackets.

That was worth it. But I was always pissed off about the opening act,

thinking I got cheated. And I once bought a Little Richard record where

he was only one track on the album. It was this other thing, the Buck

Ram Orchestra.

So we were always very conscious about that [in the Beatles]. I

remember talking to Phil Spector in the early days. Phil used to say to

us, "You guys, you put too much value on. You put an A side, and you put

a good song on the B side!" There had been a song called "Sally Go

Round the Roses," an early thing, and on the other side they'd put "Sing

Along With Sally Go Round the Roses" – just the backing track. And we'd

say, "Aw, Phil, you can't do that, man. They paid good money for this.

We would feel cheated by that." And he said, "Nah, you can do that. It's

cool." That became actually the big Beatle policy. It was always to put

a really serious B side on there – so you got "Strawberry Fields" with

"Penny Lane," and people now talk about that. That was a factor of the

Beatles' success, I think. It was always a killer B side, which people

often thought was as good or better than the A side. That was really

from the same thing of giving value for money, which George Martin used

to call "VFM."

Last night, you switched up your usual set a little – you

played "On My Way to Work," from your most recent album, without even

warning your band. Do you ever feel like doing more of that, just

tearing up the set list and playing whatever you like?Yeah,

we occasionally do that, just for the fun of it. But it's not like I'm

Phish, you know. Certainly, there's a load of people in the audience

that would want us to do that, but I have to be a bit conscious that

there's a load of people that wouldn't. Last night at the show, I said,

"I know what you think of new numbers." Because when we do the old

numbers – something like "And I Love Her" – I see all the phones come

out. You see all the little lights, ding-ding-ding-ding-ding, like

Disneyland. And why did you just get your phone out? "Because it's my

old favorite." That's reality. And like me and the Bill Haley concert, I

don't want to cheat those people. So we mix it up occasionally, but

mainly we hope we're pleasing the various facets in the audience.

People say, "But why do you care, man?" Someone like Bob Dylan

doesn't necessarily care – he'll just do what he wants, and that's cool.

I say, "Yeah, but I have these memories that haunt me of these concerts

that I went to and these records that I bought." I don't want those

people in my audience thinking, "Hey, we came for big hits, and you

played a bunch of shit."

Your friend Eric Clapton recently said he's thinking about retiring from touring. Does that idea have any appeal to you?Obviously,

when you get to a certain age, it's going to be on the cards. I had a

manager once who advised me to retire when I was 50. He said, "You know,

I'm not sure it's seemly for a 50-year-old guy to keep on trying." I

thought about it for a second and thought, "Nah." When will you give up?

When will it give out? Who knows? But the margin has been stretched

these days. The Stones go out now, and I go to their show and I think,

"It doesn't matter that they're old gits. They can play great." And I

talk to young kids who say exactly the same thing: "They play good."

I think that's the deciding factor. It would be a pity if Eric retires, because, shit, he really

plays good! But he's that kind of guy, Eric. I can see him saying, "I'm

going to retire." He's kind of a homebody in essence. We've talked

about this before. I remember him joking about how I stand up for the

whole show. He said, "I sit down." That's a blues player thing. But he's

just too good a player. I would say to him, "Yeah, by all means, sit

down, Eric. But don't retire."

A lot of people get fed up with life on the road, particularly when

you've got a really nice home life. But for me, I want it all. I've got a

great home life, and I've got a great life on the road – it's not like

we're on a Greyhound bus anymore – and the audiences are just so warm,

and the feedback is so good. People say to me, "Don't you get tired?"

It's a three-hour show, and I'm on stage every second. I keep thinking

the laws of logic ought to apply and I ought to be really tired – but

I'm invigorated. There's something about it that just gives me energy.

And there's always a day off after it, which is more than we used to

have.

Mind you, you look at the Beatles' set lists, really early days, it's

half an hour – 35 minutes if we were feeling good, 25 if we were

annoyed. [Laughs] It is, man. I used to do half lead vocal,

John would do half, so that's, like, 15 minutes each; then George would

do something, Ringo would do something, so that's even less than 15

minutes. And you were way younger, so, physically, it was nowhere near

the strain on you. But things have just grown like this, and I'm happy

with it. I like being with the band. I love playing. I play a lot more

lead guitar than I used to. I'm still learning, and that feels good. I

was saying to someone the other day that one of the very first gigs we

did – I don't even think we were the Beatles, it was the Quarrymen – one

the very first times I ever played with John, we did a very early gig

at a thing called a Co-Op Hall, and I had a lead solo in one of the

songs and I totally froze when my moment came. I really played the

crappiest solo ever. I said, "That's it. I'm never going to play lead

guitar again." It was just too nerve-wracking onstage. So for years, I

just became rhythm guitar and bass player and played a bit of piano, do a

bit of this, that and the other. But nowadays, I play lead guitar, and

that's the thing that draws me forward. I enjoy it. So, yeah, that means

the answer to "Are you going to retire?" is "When I feel like it." But

that's not today.

You just released a music video for your song "Early Days,"

where the chorus goes, "They can't take it from me if they tried/I

lived through those early days." What are you singing about there?Revisionism.

It's about revisionism, really. I know my memory has got chips in it

that still can go exactly back to two guys sitting in a room trying to

write "I Saw Her Standing There" or "One After 909." I can see that very

clearly still, and I can see every minute of John and I writing

together, playing together, recording together. I still have very vivid

memories of all of that. It's not like it fades. Since John died so

tragically, there's been a lot of revisionism, and it's very difficult

to go against it, because you can't say, "Well, no, wait a minute, man. I

did that." Because then people go, "Oh, yeah, well, that's really nice.

That's walking on a dead man's grave." You get a bit sensitive to that,

and you just think, "You know what? Forget it. I know what I did. A lot

of people know what I did. John knows what I did. Maybe I should just

leave it, not worry about it." It took a little while to get to that.

You just released a music video for your song "Early Days,"

where the chorus goes, "They can't take it from me if they tried/I

lived through those early days." What are you singing about there?Revisionism.

It's about revisionism, really. I know my memory has got chips in it

that still can go exactly back to two guys sitting in a room trying to

write "I Saw Her Standing There" or "One After 909." I can see that very

clearly still, and I can see every minute of John and I writing

together, playing together, recording together. I still have very vivid

memories of all of that. It's not like it fades. Since John died so

tragically, there's been a lot of revisionism, and it's very difficult

to go against it, because you can't say, "Well, no, wait a minute, man. I

did that." Because then people go, "Oh, yeah, well, that's really nice.

That's walking on a dead man's grave." You get a bit sensitive to that,

and you just think, "You know what? Forget it. I know what I did. A lot

of people know what I did. John knows what I did. Maybe I should just

leave it, not worry about it." It took a little while to get to that.

I know that I have every memory still intact, and they don't, as I

say in the last verse, 'cause they weren't there. I think you'll find

this in most bands, but in the Beatles' case, it's got to be worse than

any case. For instance, I was on holiday once, and there was this little

girl on the beach, little American kid. She says, "Hi, there. I've just

been doing a Beatles appreciation class in school." I said, "Wow,

that's great." I think, "I know, I'll be really cool here. I'll tell her

a little inside story." So I go on about how something happened, and it

was a fun story – and she looks at me, she says, "No, that's not true.

We covered that in the Beatles appreciation class." I'm going, "Oh,

fuck." There's no way out, man! They're teaching this stuff now.

When Sam Taylor did her film [Nowhere Boy], she brought the

script round and we chatted about it. She's a very good friend. And I

said, "Well, Sam, that's not really true. John didn't really ride on the

top of the double-decker bus." She said, "No, but it's a great scene." I

mean, the character of Mimi, John's aunt, I said to her, "She really

wasn't how she's written in the script. She's written as a very

vitriolic, mean old bitch, and she wasn't at all." She was just some

woman who was given charge of the responsibility of bringing up John

Lennon, and it was not an easy job, you know? She was trying her best.

She was kind of strict, but it was with a twinkle in her eye. I said, "I

used to go around there and write with John, and she was okay. You've

got to change that." Some of the things she did change, but in the end

we agreed that this is not a documentary, this is a film, and so she

made inferences that weren't there. Like, this whole idea of the first

song we recorded, "In Spite of All the Danger," being John's ode to his

mother. That's not true, but in a film, it works better. I remember the

session, and I remember all the circumstances around that – and we wrote

it together. It did not appear to be an angst-ridden ode. We were

copying American stuff that we were listening to. American songs were

about danger, that's why we put it in. But, for Sam, it worked much

better in the film as an angst-ridden ballad.

To get back to my original point, that's the kind of thing that

happens in films, but these books that are written about the meaning of

songs, like Revolution in the Head – I read through that. It's a

kind of toilet book, a good book to just dip into. And I'll come

across, "McCartney wrote that in answer to Lennon's acerbic this," and I

go, "Well, that's not true." But it's going down as history. That is

already known as a very highly respected tome, and I say, "Yeah, well,

okay." This is a fact of my life. These facts are going down as some

sort of musical history about the Beatles. There are millions of them,

and I know for a fact that a lot of them are incorrect.

I can see how that would be frustrating.Well, it

used to be frustrating. I've got over it. It's okay. "Early Days" has a

smattering of that, but the main thing is it's a memory song. It's me

remembering walking down the street, dressed in black, with the guitars

across our back. I can picture the exact street. It was a place called

Menlove Avenue. [Pauses] Someone's going to read significance into that: Paul and John on Menlove Avenue. Come onnnnnnn. That's

what it's like with the Beatles. Everything was fucking significant,

you know? Which is okay, but when you were a part of the reality, it

just wasn't like that. It was much more normal.

No comments:

Post a Comment