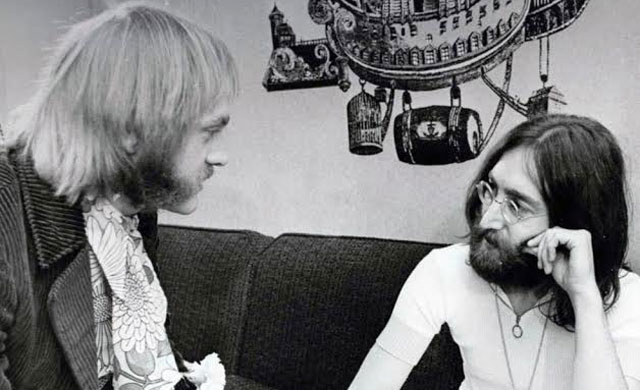

Ritchie Yorke with John Lennon at the King Eddie hotel in Toronto discussing the location for John and Yoko's second bed-in for peace which ultimately took place in Montreal, May 1969.

As a 19-year-old in 1963, Ritchie Yorke locked himself in the studio of

a Toowoomba radio station and played Little Stevie Wonder's "Fingertips

Pt 2" eight times in a row. The on-air protest was an answer to the

program manager's threat that he stop playing “nigger music” on his

Saturday night rock ‘n’ roll show or face the sack, and had station

staff not beaten down the door, Ritchie would have repeated the track

indefinitely. At the time, no one realised that he would go on to become

on of the world's most respected music journalists, making Editor of

Rolling Stone, rubbing shoulders with Jimi Hendrix and Aretha Franklin,

becoming friends with John and Yoko, and going on tour with Led

Zeppelin. In fact, he still has Jimi's hat after being given it as a

gift for appearing as a character witness for the guitarist in a Toronto

courtroom, the city he moved to after the unsavory incident on regional

Australian radio.

So starting from the beginning, what happened with your radio show in Brisbane that prompted you to leave Australia?

Ritchie Yorke: Well it was 1963 and I’d gotten a job

as a copywriter at a radio station in Toowoomba. A crucial part of the

deal for me was that I had my own rock ‘n’ roll show on Saturday nights.

At the time I was on the mailing list with Motown Records so every

couple of weeks I would get a package with all the latest singles they

had released.

On one of those days I received a record called "Fingertips Pt 2" by

this guy called Little Stevie Wonder. It turned out that he was a

12-year-old blind kid. It became an instant hit in America and went to

number one. I was impressed, not only by that, but because this was the

most unbelievable record I’d ever heard in my life—I couldn’t wait to

play it on the air. On the following Monday morning I was called into

the program manager's office where he told me they weren’t too impressed

with the sort of music I was playing. They didn’t want any of this

“nigger music” or they would kick me out.

The following Saturday night I locked myself in the studio and played

it again, only this time I played it eight times in a row before they

got down there and fired me—that was the end of that job!

What made you do that?

Well I felt a line needed to be drawn. This was music history! And it was absolutely brilliant music.

Well I felt a line needed to be drawn. This was music history! And it was absolutely brilliant music.

Was there much black music being played at that time?

Hardly any at all. Australia in 1963 was basically a black music free zone. They didn’t touch anything that remotely resembled rhythm and blues, especially the big city stations. It was sad but that’s the way it was here for a long time.

Hardly any at all. Australia in 1963 was basically a black music free zone. They didn’t touch anything that remotely resembled rhythm and blues, especially the big city stations. It was sad but that’s the way it was here for a long time.

Did you always want to write about music? And do you think music journalism has changed since those days?

It was always about music journalism for me and yeah it has

changed—it’s totally controlled now. Back in those days you hustled to

get your own interviews, you hung around with the artist and their

friends and built favour with them. Now days it’s all pre-arranged and

planned: “You’ve got 20 minutes with so-and-so tomorrow at noon.” It’s

all corporatised and your assigned slots are based on the circulation of

your paper or listenership of your radio show. It was much looser then

than it is now.

During the late 60s you struck up a friendship with John Lennon. How did that comes about?

I met John in ’68 while working for The Globe and Mail in Toronto, which is Canada’s national newspaper. I was their first full-time rock writer. I used to make long weekend trips to London. I would head over on the Friday and do interviews, then fly back on the Monday or Tuesday. I met John once or twice and discovered that we had a lot of things in common and I really liked what he was trying to do.

I met John in ’68 while working for The Globe and Mail in Toronto, which is Canada’s national newspaper. I was their first full-time rock writer. I used to make long weekend trips to London. I would head over on the Friday and do interviews, then fly back on the Monday or Tuesday. I met John once or twice and discovered that we had a lot of things in common and I really liked what he was trying to do.

John was emerging in his own right. It was the early days of John and

Yoko together and John was anxious to make his own statement. I was very

impressed by what he was trying to say—I joined in his corner and

became one of the people he could call on to help spread his word.

How long after meeting him were you asked to become the Peace Envoy for the “War Is Over! (if you want it)” campaign?

Probably about a year. That came after we had already worked on a few peace/music projects together. I became John and Yoko's “go-to man” in Canada. It was a very fortunate experience for me. John couldn’t get into the US at that time because he was busted a few months earlier in London for possession of a piece of hash planted in his flat by a crooked cop.

Probably about a year. That came after we had already worked on a few peace/music projects together. I became John and Yoko's “go-to man” in Canada. It was a very fortunate experience for me. John couldn’t get into the US at that time because he was busted a few months earlier in London for possession of a piece of hash planted in his flat by a crooked cop.

I steered John and Yoko to Montreal in ’69, where they recorded “Give

Peace a Chance” in their hotel room during their second “Bed-In” for

peace. They had quite a few connections with Canada. He returned in July

after he’d been offered a chance to perform with some of the great rock

‘n’ roll people he loved at the Toronto Rock ‘n’ Roll Revival. I

happened to be in his office in London when he got the call and as fate

would have it, I was able to convince him to give it a go.

So for the first time in four years a member of the Beatles got out on

stage and performed. After returning from that trip, John told the rest

of the band that he’d discovered he didn’t need them anymore. He could

perform without them on stage and he intended to go out on his own.

Later on that year he launched the“War is Over” campaign and came back

to Canada, where I introduced him to the Prime Minister. That was the

beginning of political pop—it was the first time in history a pop star

had met a Prime Minister.

Ritchie Yorke and partner Minnie Cherry with Yoko Ono at the Sydney

Opera House following her performance to accompany the opening of her

War is Over exhibition at the museum of contemporary art, Nov. 2013.

Do you remember where you were when John died?

I certainly do. I was living in a little country town called Erin, about an hour outside of Toronto, when I got a phone call. It was about 11 o’clock at night and a friend had heard a radio news flash saying that John Lennon had been shot. I don’t think I’ve ever been quite the same since. I think a part of all of us died in that moment—the caring part. How can a man involved in peace be shot?!

I certainly do. I was living in a little country town called Erin, about an hour outside of Toronto, when I got a phone call. It was about 11 o’clock at night and a friend had heard a radio news flash saying that John Lennon had been shot. I don’t think I’ve ever been quite the same since. I think a part of all of us died in that moment—the caring part. How can a man involved in peace be shot?!

No comments:

Post a Comment