It's

no surprise that John Lennon harbored some ill will toward Paul

McCartney in the aftermath of the Beatles' breakup. In the new book The John Lennon Letters, a

previously seen handwritten 1971 note from John and Yoko On0 to Paul

and his wife Linda (whom Lennon sarcastically addressed as "you noble

people") confirms what everyone already knows about that enmity, as

Lennon chides McCartney to "get off your gold disc and fly!"

What's not so well known: the tiff between Lennon and producer George

Martin, a beloved figure not usually known for his participation in

Beatle beefs.

"The John Lennon Letters"In one of the angrier missives included in The John Lennon Letters,

the then-bitter ex-Beatle lays into Martin for supposedly taking too

much credit for the group's sound. He also smacks the producer down for

giving McCartney too much credit for some of the songwriting.

"The John Lennon Letters"In one of the angrier missives included in The John Lennon Letters,

the then-bitter ex-Beatle lays into Martin for supposedly taking too

much credit for the group's sound. He also smacks the producer down for

giving McCartney too much credit for some of the songwriting.

"When people ask me questions about 'What did George Martin really do for you?,' I have only one answer, 'What does he do now?' I noticed you had no answer for that! It's not a putdown, it's the truth," wrote Lennon, who had brought in Phil Spector to redo Martin's work on Let It Be and then continued to work with Spector as a solo artist.

"I think Paul and I are the best judges of our partners," Lennon

wrote, less than politely. "Just look at the world charts and, by the

way, I hope Seatrain is a good substitute for the Beatles."

Can you say "snap, squared"? Seatrain, as very few people will

recall, was the unremarkable California roots-rock band Martin was

assigned to produce by Capitol Records immediately after the Beatles'

breakup.

What angered Lennon so? In the larger sense, armchair psychologists

might suppose that a would-be "working class hero" like Lennon possibly

harbored some resentment over having his musical revolution seen as

reliant on a stiff-upper-lip establishmentarian like Martin. But in the

immediate sense, Lennon was reacting to a Melody Maker interview in

which Martin made some seemingly innocent remarks that got the rocker's

considerable gander up.

"Now on to 'Revolution No. 9,' which I recorded with Yoko plus the help of Ringo, George and George Martin. It was my concept, fully," Lennon wrote in a letter co-addressed to the Melody Maker interviewer. "For

Martin to state that he was 'painting a sound picture' is pure

hallucination. Ask any of the other people involved. The final editing

Yoko and I did alone (which took four hours)...

George Martin and Lennon, in seemingly happier times"Of

course, George Martin was a great help in translating our music

technically when we needed it, but for the cameraman to take credit from

the director is a bit too much. I'd like to hear what the producer of

John Cage's 'Fontana Mix' would say about that... Don't be so paranoid,

George, we still love you," ended the main part of the note, signed by "

John (and Yoko who was there)."

George Martin and Lennon, in seemingly happier times"Of

course, George Martin was a great help in translating our music

technically when we needed it, but for the cameraman to take credit from

the director is a bit too much. I'd like to hear what the producer of

John Cage's 'Fontana Mix' would say about that... Don't be so paranoid,

George, we still love you," ended the main part of the note, signed by "

John (and Yoko who was there)."

Looking back at Martin's 1971 Melody Maker, it's not hard to pick out

some other passages that might have set Lennon off. "John's become more

obvious in a way," Martin told the British music weekly, then a bit

less circumspect than he later became. "'Power To The People' is a

rehash of "Give Peace A Chance," and it isn't really very good. It

doesn't have the intensity that John's capable of. Paul, similarly with

his first album ... it was nice enough, but very much a home-made

affair, and very much a little family affair. I don't think he ever

really rated it as being as important as the stuff he'd done before. I

don't think Linda is a substitute for John Lennon, any more than Yoko is

a substitute for Paul McCartney."

Martin managed to step into a dispute over authorship that continues

to confound Beatles fans to this day when he was asked if he remembered

anything about the writing of "Eleanor Rigby." "Not the song, but I do

remember the recording taking place. I had assumed that it was all

Paul," Martin told Melody Maker. "In fact I do remember, actually at the

recording Paul was missing a few lyrics, and wanting them, and going

round asking people 'What can we put in here?' and Neil (Aspinall) and

Mal (Evans) and I were coming up with suggestions. Rather petty,

really... everyone contributed things occasionally."

Lennon bristled at that, big-time, in a P.S. "At least 50% of the

lyrics of 'Eleanor Rigby' was written by me in the studio and at Paul's

place, which was a fact never clearly indicated in your previous

article."

(Estimating percentages can be an unwise errand, as Mitt Romney

recently learned the hard way. After claiming credit for "at least 50%"

of the "Rigby" lyrics in this note, a year later, Lennon told Hit

Parader, "I wrote a good lot of the lyrics, about 70 per

cent." McCartney responded, "I saw somewhere that he says he helped on

'Eleanor Rigby.' Yeah. About half a line. He also forgot completely that

I wrote the tune for 'In My Life.' That was my tune. But perhaps he

just made a mistake on that." Many years later, a more

magnanimous McCartney came up with a slightly more generous ratio: "John

helped me on a few words but I'd put it down 80-20 to me, something

like that.")

But there were bigger issues at play than just one song. Last year,

in an interview with London's Independent newspaper, Martin talked about

what he considered the ultimate insult from Lennon: hearing Lennon say

that he wished they could re-record every song the Beatles ever put on

tape.

"I said to him: 'I can't believe that. Think of all we've done and

you want to rerecord everything?' 'Yeah, everything.' And I said: 'What

about 'Strawberry Fields'?' And he looked at me and said: 'Especially

'Strawberry Fields'.' Which I was very disappointed with. If he felt

that way about it, he should have recorded the bloody thing himself."

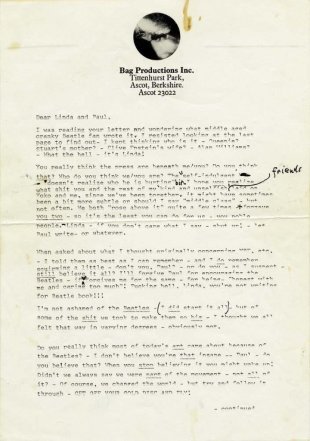

Page 1 of John and Yoko's letter to Linda and PaulOf

course, it's Lennon's previously revealed broadsides against McCartney

that will again get the most attention with the release of The John Lennon Letters.

Linda McCartney had written a letter to John about some of his public

statements about Paul, and Lennon told her to "get off your high horse."

Page 1 of John and Yoko's letter to Linda and PaulOf

course, it's Lennon's previously revealed broadsides against McCartney

that will again get the most attention with the release of The John Lennon Letters.

Linda McCartney had written a letter to John about some of his public

statements about Paul, and Lennon told her to "get off your high horse."

"I was reading your letter and wondering what middle-aged cranky

Beatle fan wrote it. I resisted looking at the last page to find out...

What the hell—it's Linda!... Who do you think we/you are? The

'self-indulgent doesn't realize who he is hurting' bit—I hope you realize

what s--- you and the rest of my 'kind and unselfish' friends laid on

Yoko and me, since we've been together. It might have sometimes been a

bit more subtle or should I say 'middle class'—but not often. We both

'rose above it' quite a few times—& forgave you two—so it's

the least you can do for us, you noble people. Linda, if you don't

care what I say, shut up! Let Paul write—or whatever."

In talking about the Beatles' breakup, Lennon even seemed to

insinuate that McCartney was destined to divorce himself from the

Eastman family, if not Linda herself. "About not telling anyone that I

left the Beatles: PAUL and Klein both spent the day persuading me it was

better not to say anything—asking me not to say anything because it

would 'hurt the Beatles'— and 'let's just let it peter out'—remember? So

get that into your petty little perversion of a mind, Mrs. McCartney:

the [expletives] asked me to keep quiet about it. Of course,

the money angle is important—to all of us— especially after all the

petty s-- that came from your insane family/in-laws. And GOD HELP YOU

OUT, PAUL. See you in two years. I reckon you'll be out then..."

Lennon didn't reserved his zingers just for ex-compatriots, as the letters show.

On a postcard to an anti-Yoko fan, he wrote, "Why don't you open your box and dig 'Mind Train' on (Ono's album) Fly—your prejudice can't be that deep... P.S. YOU might have an ageing (sic) problem. Me? I wouldn't go back ONE DAY!"

A review of Ono's art installation by the Syracuse Post-Standard

brought about a memorable letter to the editor, in which he resented

being brought up in the criticism. "What on earth has what the husband

of the artist said, four or five years ago, got to do with the current

[show] by Yoko Ono?... I mean, did people really discuss Picasso's

wife's gossip?" He went on to refer to the criticism as

"bourgeoisie mealy-mouth gossip" from "blue meanies."

He could be fairly tongue-in-cheek even when he was angry... and also

get in a good product plug. Writing to Melody Maker (again) after a

joint interview with Ono, he scribbled, "She never, but never, wears clogs (or anything resembling clogs) on her most divine and beautiful little feet!

(This is shown by sexy Polaroid Lennon photograph of Yoko's above

mentioned extremities on back of her fantastic new double-album Fly…)"

As fans know, Lennon mellowed considerably in the latter half of the

'70s, and had his rapprochement with McCartney, if any eventual

communiques with Martin are lesser known. But "Tell us what you really

think, John" was surely even then never uttered in anything but jest.

PLAYBOY: ”When you talk about working together on a single lyric like ‘We Can Work It Out,’ it suggests that you and Paul worked a lot more closely than you’ve admitted in the past. Haven’t you said that you wrote most of your songs separately, despite putting both of your names on them?”

ReplyDeleteLENNON: ”Yeah, I was lying. (laughs) It was when I felt resentful, so I felt that we did everything apart. But, actually, a lot of the songs we did eyeball to eyeball.” Playboy 1980